I have written a lot about emotional intelligence over the years. Several years ago we brought emotional intelligence coaching into our practice and have seen how it has been able to help improve the professional and personal lives of the professionals that we have coached.

The two foundational elements of emotional intelligence are self-awareness and empathy. Recognition, practice, and mastery of these two elements will help professionals to better optimize the potential within them. As it has always been said, skill alone will not lead you to success.

I recently re-visited the topic of self-awareness by reading an excellent Harvard Business Review article “What Self-Awareness Really Is (and How to Cultivate It)” by Tasha Eurich. In her article, Dr. Eurich provides a deep analysis on what self-awareness really is, why we need it, and how we can increase it.

In her HBR article, Dr. Tasha Eurich discusses the initial finding of the research that she has completed that involved a large-scale scientific study of self-awareness. In 10 separate investigations with nearly 5,000 participants. Some insights from her researched showed that

… most people believe they are self-aware, self-awareness is a truly rare quality: We estimate that only 10%–15% of the people we studied actually fit the criteria.

The analysis from her research led to three findings:

- There Are Two Types of Self-Awareness

- Experience and Power Hinder Self-Awareness

- Introspection Does Not Always Improve Self-Awareness

There Are Two Types of Self-Awareness

The results of Dr. Eurich’s studies showed that there two categories of self-awareness:

Internal self-awareness - which represents how clearly we see our own values, passions, aspirations, fit with our environment, reactions (including thoughts, feelings, behaviors, strengths, and weaknesses), and impact on others. We’ve found that internal self-awareness is associated with higher job and relationship satisfaction, personal and social control, and happiness; it is negatively related to anxiety, stress, and depression.

External self-awareness – which means understanding how other people view us, in terms of those same factors listed above. Our research shows that people who know how others see them are more skilled at showing empathy and taking others’ perspectives. For leaders who see themselves as their employees do, their employees tend to have a better relationship with them, feel more satisfied with them, and see them as more effective in general.

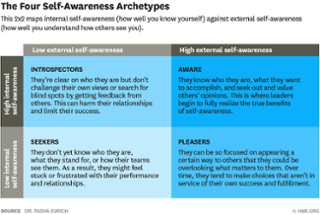

The interesting insight in Dr. Eurich’s research is that being high on one type of awareness does not necessarily mean that you will be high on the other. Her studies showed that there are four leadership archetypes that emerge:

Courtesy of: Dr. Tasha Eurich and Harvard Business Review

The conclusion is not having one level of self-awareness, either internal or external, is not enough. There may be a false sense of assurance that you are completely self-aware when in fact blind spots exist.

- You may have an honest self-assessment of your strengths and weaknesses but do not understand completely how others see you.

- You also have to understand how you are seen by others but not really be sure who you really are.

At The Frontier Group, we are able to see this dynamic play out often during our executive coaching sessions where we are able to have participants go through a thorough 360 review process. The 360 process quite often provides great external feedback that we can then match with our one-on-one internal self-awareness coaching sessions.

The bottom line is that self-awareness isn’t one truth. It’s a delicate balance of two distinct, even competing, viewpoints.

Experience and Power Hinder Self-Awareness

An interesting dynamic that has shown up in research on emotional intelligence (EQ) is that senior management often has less EQ than their middle management.

Dr. Eurich explains it this way:

Contrary to popular belief, studies have shown that people do not always learn from experience, that expertise does not help people root out false information, and that seeing ourselves as highly experienced can keep us from doing our homework, seeking disconfirming evidence, and questioning our assumptions.

And just as experience can lead to a false sense of confidence about our performance, it can also make us overconfident about our level of self-knowledge.

For example, one study found that more-experienced managers were less accurate in assessing their leadership effectiveness compared with less experienced managers.

Even though most people believe they are self-aware, only 10-15% of the people we studied actually fit the criteria.

Similarly, the more power a leader holds, the more likely they are to overestimate their skills and abilities. One study of more than 3,600 leaders across a variety of roles and industries found that, relative to lower-level leaders, higher-level leaders more significantly overvalued their skills (compared with others’ perceptions). In fact, this pattern existed for 19 out of the 20 competencies the researchers measured, including emotional self-awareness, accurate self-assessment, empathy, trustworthiness, and leadership performance.

Researchers have proposed two primary explanations for this phenomenon.

First, by virtue of their level, senior leaders simply have fewer people above them who can provide candid feedback.

Second, the more power a leader wields, the less comfortable people will be to give them constructive feedback, for fear it will hurt their careers. Business professor James O’Toole has added that, as one’s power grows, one’s willingness to listen shrinks, either because they think they know more than their employees or because seeking feedback will come at a cost.

But this doesn’t have to be the case. One analysis showed that the most successful leaders, as rated by 360-degree reviews of leadership effectiveness, counteract this tendency by seeking frequent critical feedback (from bosses, peers, employees, their board, and so on). They become more self-aware in the process and come to be seen as more effective by others.

Likewise, in our interviews, we found that people who improved their external self-awareness did so by seeking out feedback from loving critics — that is, people who have their best interests in mind and are willing to tell them the truth. To ensure they don’t overreact or overcorrect based on one person’s opinion, they also gut-check difficult or surprising feedback with others.

Introspection Doesn’t Always Improve Self-Awareness

Dr. Eurich also has very interesting insights that challenge the conventional wisdom that introspection leads to greater self-awareness. Her reasoning is that introspection is not necessarily ineffective but that most people approach it the wrong way.

The problem with introspection isn’t that it is categorically ineffective — it’s that most people are doing it incorrectly. To understand this, let’s look at arguably the most common introspective question: “Why?” We ask this when trying to understand our emotions (Why do I like employee A so much more than employee B?), or our behavior (Why did I fly off the handle with that employee?), or our attitudes (Why am I so against this deal?).

The problem with introspection isn’t that it is ineffective—it’s that most people are doing it incorrectly.

As it turns out, “why” is a surprisingly ineffective self-awareness question. Research has shown that we simply do not have access to many of the unconscious thoughts, feelings, and motives we’re searching for. And because so much is trapped outside of our conscious awareness, we tend to invent answers that feel true but are often wrong. For example, after an uncharacteristic outburst at an employee, a new manager may jump to the conclusion that it happened because she isn’t cut out for management, when the real reason was a bad case of low blood sugar.

Consequently, the problem with asking why isn’t just how wrong we are, but how confident we are that we are right. The human mind rarely operates in a rational fashion, and our judgments are seldom free from bias. We tend to pounce on whatever “insights” we find without questioning their validity or value, we ignore contradictory evidence, and we force our thoughts to conform to our initial explanations.

Dr. Eurich makes an excellent recommendation that effective introspection should begin with asking “what” not “why”. Her rationale is that by asking what we allow ourselves to remain more objective, internalize less, and become more confident to act. Instead of the mounting self-criticism that comes from asking “why” we can ask “what” are the situations and actions that are caused the issue and how can they be corrected.

Self-awareness isn’t one truth. It’s a delicate balance of two distinct, even competing, viewpoints.

All of this brings us to conclude: Leaders who focus on building both internal and external self-awareness, who seek honest feedback from loving critics, and who ask what instead of why can learn to see themselves more clearly — and reap the many rewards that increased self-knowledge delivers. And no matter how much progress we make, there’s always more to learn. That’s one of the things that makes the journey to self-awareness so exciting.

About the Contributing Author

Tasha Eurich, PhD, is an organizational psychologist, researcher, and New York Times bestselling author. She is the principal of The Eurich Group, a boutique executive development firm that helps companies—from start-ups to the Fortune 100—succeed by improving the effectiveness of their leaders and teams. Her newest book, Insight, delves into the connection between self-awareness and success in the workplace.

![]()